Creating is scary. It’s intimidating. It’s lonely. It induces self-doubt and procrastination.

No one I know of speaks more honestly and memorably on the struggles of being an artist than the writer Anne Lamott. In her book, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, Lamott offers advice to writers (and other artists) in how to overcome the blocks that we put in our own way, preventing us from actually doing the work we love so much. Lamott’s clear-headed and humorous counsel encourages artists of all types.

During my classes I often read selections from “Bird by Bird.” Especially for beginners, creating a fabric collage quilt can be intimidating. Students often have little or no formal training in art. Translating the vision they have in their heads to fabric and thread can be a steep climb up an icy slope. They need both tools and encouragement to reach the peak. I give them the tools—Lamott helps me give them encouragement.

The title of the book itself urges us to put the task at hand in proper perspective. Lamott relates the story of her ten-year-old brother, who had put off to the last day his assignment to write a report about “birds”:

We were out at our family cabin in Bolinas, and he was at the kitchen table close to tears, surrounded by binder paper and pencils and unopened books on birds, immobilized by the hugeness of the task ahead. Then my father sat down beside him, put his arm around my brother’s shoulder, and said, “Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird.”

My students often need to be reminded that when confronted with a blank piece of muslin their task isn’t to create a completed quilt. It’s to put the first piece of fabric down—and then the next—and then the next. Use whatever terms you like—step by step, bit by bit—but since reading Lamott I always first think “bird by bird.”

Sometimes a student remains unconvinced. Perhaps they’ve always worked from a pattern or even a complete quilt kit. They may be used to knowing exactly what the quilt is going to look like before they even start. That just ain’t the way fabric collage (the way I do it) works. Helping them overcome this mindset then becomes one of my most important jobs.

Here’s a passage I sometimes refer to:

E.L. Doctorow once said that “writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” You don’t have to see where you’re going, you don’t have to see your destination or everything that you will pass along the way. You just have to see two or three feet ahead of you. This is right up there with the best advice about writing, or life, I have ever heard.

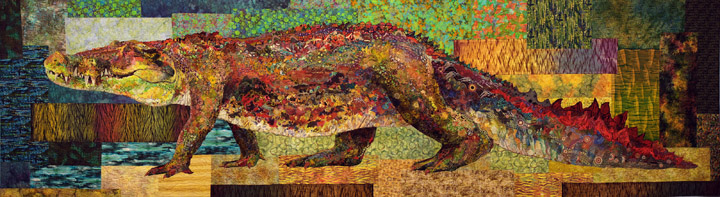

In a previous blog, I talked about how I didn’t know exactly what my quilt “Crocodylus Smylus” would look like when completed. Sometimes you just have to “leap before you look.” I had to have faith that if I kept going I would reach my goal.

As we shine our headlights down this winding road of creativity, there are signposts along the way. As a writer, Lamott thinks in drafts, with each representing a stage of the journey, which helps discourage excessive perfectionism too early in the process. In fabric collage, it’s impossible to know for certain whether that first piece of fabric you use is actually the right one. It might not be. It might have to be covered up or replaced once you make some progress. But that first piece of fabric is important even if it turns out to be wrong:

Almost all good writing [or fabric collage] begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere. Start by getting something—anything—down on paper [or muslin]. A friend of mine says that the first draft is the down draft—you just get it down. The second draft is the up draft—you fix it up. You try to say [show] what you have to say [show] more accurately. And the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it’s loose or cramped or decayed, or even, God help us, healthy.

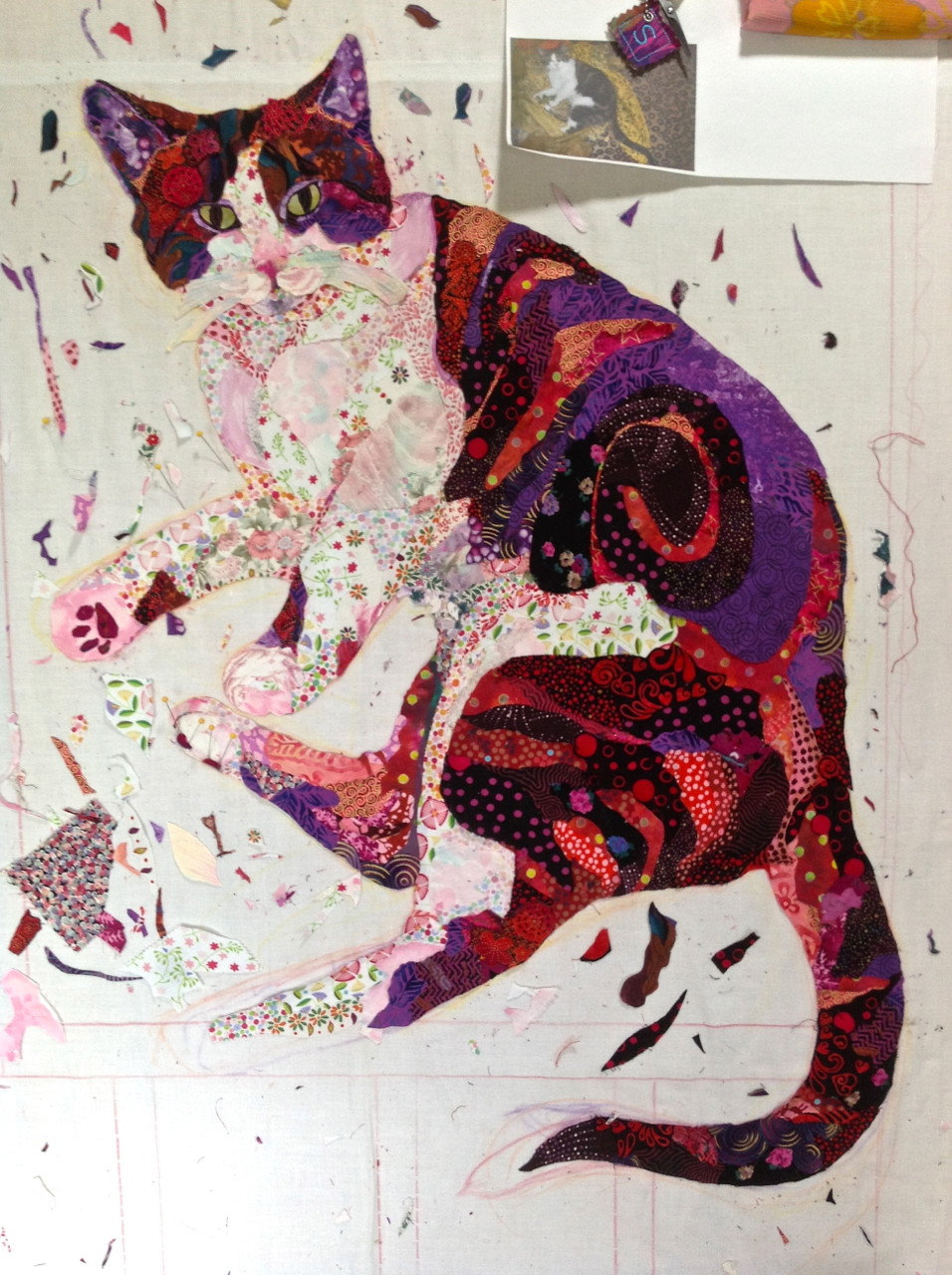

You have to start somewhere, and it’s often the hardest part. So you put a piece of fabric here, and another one there, and it starts to look like it’ll never work. I refer to this beginning of the down draft as the “messy-scary” stage. And it can be daunting.

Kali the dog at the messy-scary stage is hard to imagine as a cute white mini-Schnauzer. It’s at this point that some novices run into a wall. Heck, I do, too. It’s hard to believe that it will ever look any better.

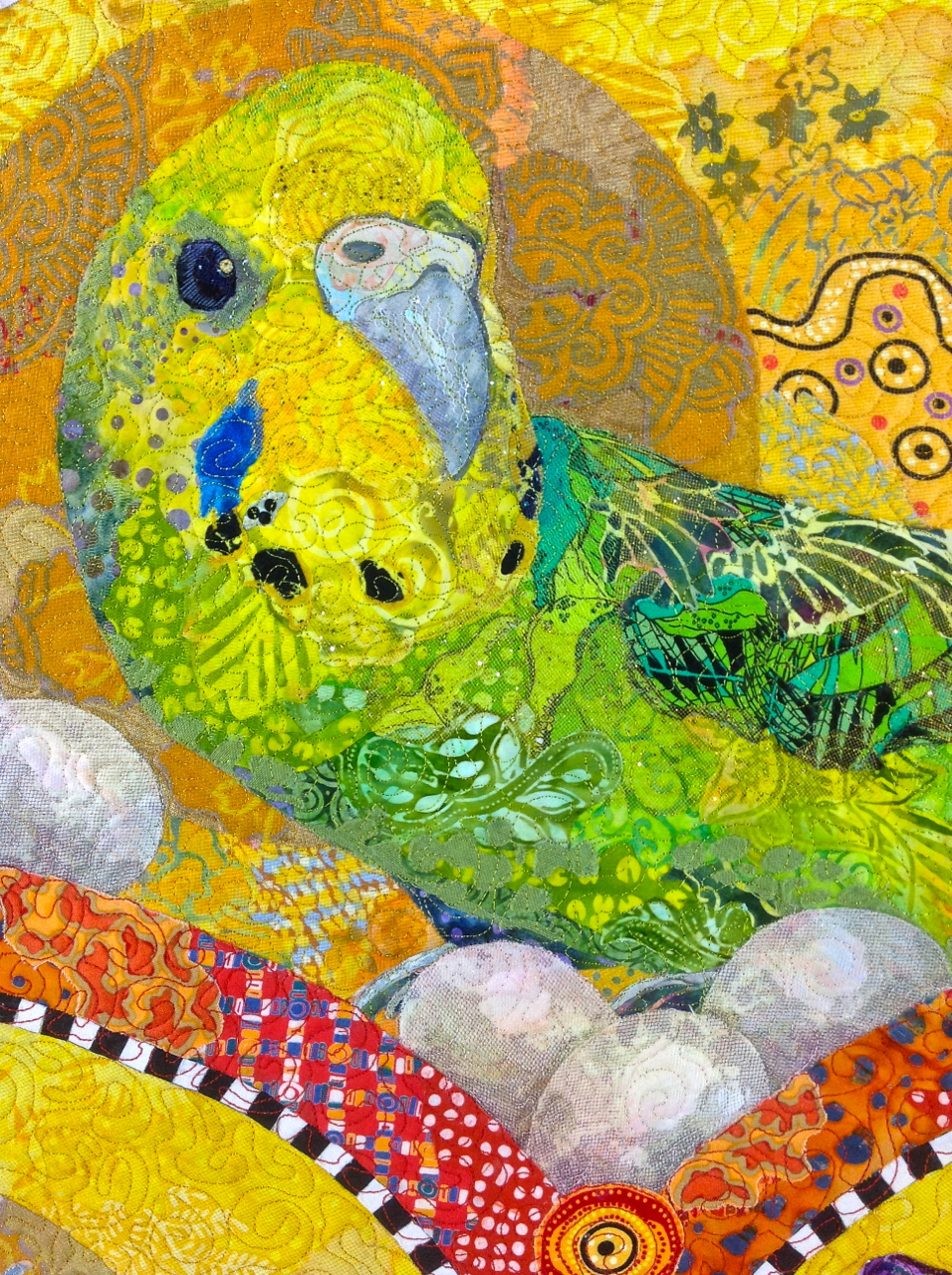

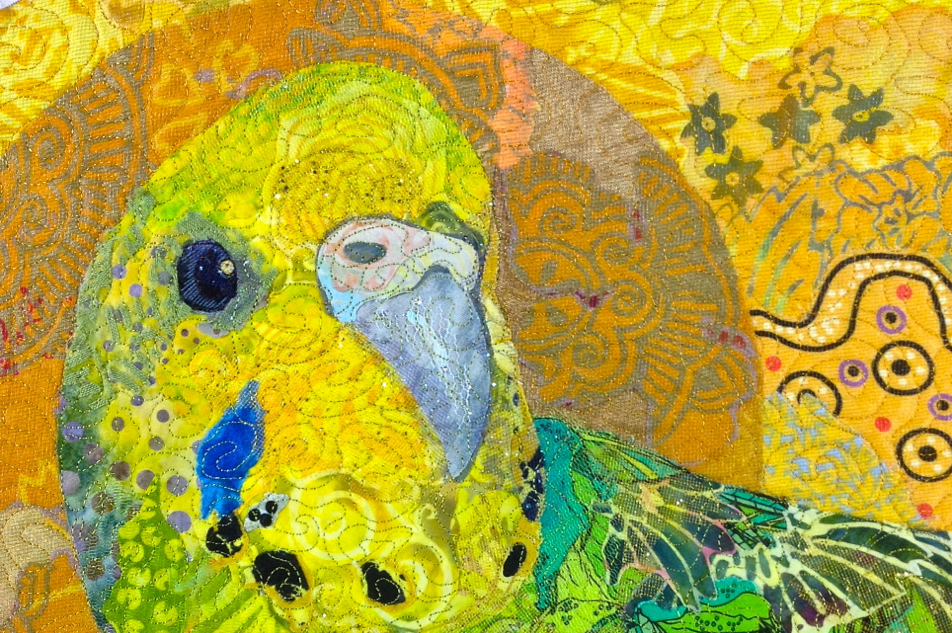

But when we keep going we eventually reach—or pass through—the down draft. The piece is blocked in. The big picture is coming clear. The muslin is covered. Here are Djinni the cat, Kali the dog, and Kiiora the budgie at the finish of the down draft:

Art—whether writing or visual—isn’t formulaic. My quilts—and I suspect Lamott’s books—don’t always follow a structured and organized path to completion.

Kali the dog hit each signpost pretty much on schedule—down draft, up draft, and dental draft.

Kiiora the budgie flowed together with hardly any hitch. The down draft and updraft happened almost simultaneously. Then it was on to the final tweaks of the dental draft.

Images that flow together like Kiiora the budgie did are the exception. Often, at some point, there’ll need to be a fairly major revision. I revised the front leg of “Crocodylus Smylus” three times before I was satisfied. Djinni cat was another example. While working on the background, it became clear to me that her tail blended in too much. What to do? Where are my headlights? Ahhh, I see, it needed to be moved to a different angle.

Once the tailectomy was complete I could work on finishing Djinni as I had the other two, adding final detail, and boosting highlights and shadows with tulle and other translucent fabrics. Plus that sparkle.

Each subject in “Golden Temple of the Good Girls” followed a different path to completion. I’m sure Lamott would agree that that’s the nature of creativity. If the experience of creating were the same each time, it would cease being art. It would be manufacturing.

On the other hand, being an artist isn’t all about the mystery of creation. Much of it is simply hard work. Choose your metaphor—birds, headlights, drafts—whatever inspires you to stick to it. There are no shortcuts. In the end, there’s no substitute for just doing the work.

“But once I’ve done the work, how do I know when a piece is done?” Students ask this all the time. Only they will know for certain.

Lamott gives us a vivid image to help us make that decision. She says it’s like “putting an octopus to bed”:

You get a bunch of the octopus’ arms neatly tucked under the covers…but two arms are still flailing around. But you finally get those arms under the sheet, too, and are about to turn out the lights when another long sucking arm breaks free… if you know that there is simply no more steam in the pressure cooker and that it’s the very best you can do for now—well? I think this means you are done.

Well? I think this means I’m done. I’ve put the octopus to bed on this blog post.

(All quotes are from Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life by Anne Lamott © 1994.)

NEXT WEEK: Using Value to Create Whimsical Color Palettes

A follower of this blog asked if I would talk about how I use non-realistic colors in my quilts while making the subjects “lifelike.” Next week I tackle this topic.

Amazing! I’m getting my muslin out today so I can begin.

Thanks Susan clarifies a lot for me.

Great suggestions about getting the job done. May I also highly recommend a short book called “The War of Art” by Steven Pressfield (also available on Audible) which addresses the importance of making yourself sit down and making yourself do your work – whatever that work is – any creative endeavor! Inspiration and talent are wonderful things, but neither matters if you put off beginning in the first place. You know in your heart what you’re supposed to be doing – so go do it now!

I listened to The War of Art as an audio book as I was finishing up my latest quilt. It’s a good one.

Excellent post….I love “Bird by Bird”. But I haven’t read it for a while. You clearly put a lot of effort into your blog writing. And the pictures of your work in progress are fantastic.

I really appreciate this inspirational post and peek inside your creative process.

I have a journal kept by a relative who was an Iowa farm girl in the very early 1900s. Her journal was filled with meeting friends, cooking, sewing, etc., but on many days the entry was, “Just did the work.” Remembering this, reading your post, and recalling the words of Anne Lamott are inspiring me to go get some things done… I thank you!

Thank you for explaining your processes Susan, the penny has dropped! I really appreciate your blogs and the time you put into them. Your work is really inspirational especially to someone who has had no art training and always felt I had no artistic ability.

Creativity: a mystery and work. That about nails it! And just do it. Great post! I just finished a hooked art hanging and someone asked how I did the background. I just did it and it came out. Hard to explain the process sometimes. You explained your very well!

Great Post! I read Bird by Bird for inspiration as well. I definitely apply the courage of squashing “suppose to and should” out of my creative palette`- be it with ingredients while cooking, words when writing, notes when playing music and with anything I stitch. It’s a win-win combo in my eyes.

I adore the parakeet you created. I simply must attempt this. Yours is AMAZING. Most of my life I have enjoyed parakeets as one of my pets. My current cat is terribly curious aka jealous of my last bird – and low ceilings have kept me from buying a new bird since Lili Bee died. Anyway, thank you for sharing your creative process!

Fantastic post. This is me to a tee. I am often frightened when start a new project, especially those with an “Artsy Flair”. I just fall in love with any Collage Quilts I see. Looking forward to reading “Bird by Bird”. You are truly an inspiration.

I’ve been reading your book, while dreaming about making a “collage quilt.” I’m such a follower of organization and process that beginning scares me to death. This post has helped me immensely. Thank you for describing how to begin.

Hi Susan,

Thank you so much for this inspirational post about the struggles of creating. I love that you share so honestly your process of creating and your inspirational sources. I am new to collage, but my job is to write and I feel there are many crossover skills in this two artforms, and your post just came at the perfect time and place for me because I am currently struggling with starting writing a new chapter ! Thank you again ☺️