Sequence in Fabric Collage Part 1: Fabric Collage By the Numbers #7

I hate to sound all controlling and rule-bound, because that’s not how I believe art should happen, but there is an “optimal” order in which to fill in the layers of your fabric collage. When I say optimal I mean the “most useful” or “most helpful” way of working with smaller pieces of fabric. And I also mean, from my the decades of experience, most logical. Why make the process more complicated than you need to?

But sequence, as I call this way of thinking, isn’t always intuitive, though it becomes more so the more you work with it. You’ll have to take my word for this—that working “top down” is the way to approach a fabric collage, even if at first it may seem just plain backward.

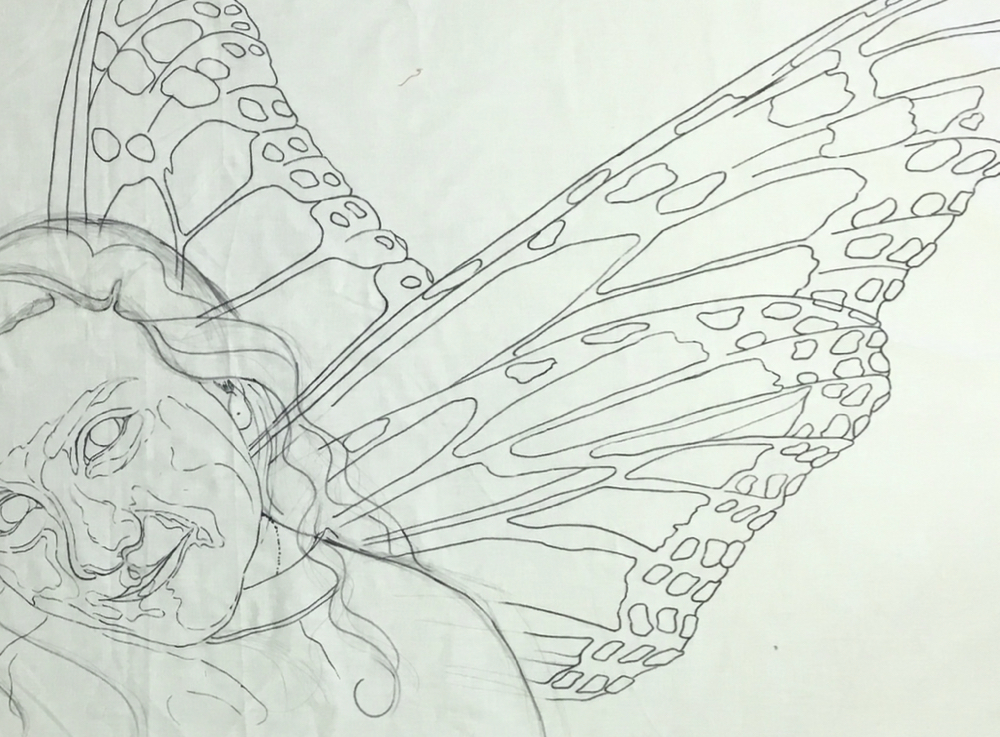

Take, for example, the monarch butterfly wing in my quilt “Monarch Maia” seen in-progress above. I’ve found that many people are tempted to first cut a basic shape of the wing in black fabric, then place the orange shapes on top of it. In this week’s revisited post “Sequence in Fabric Collage Part 1” I explain how I created the orange shapes in the wing first and then filled in the spaces between them with a variety of black fabrics.

Is that logical? Check out this week’s Sequence in Fabric Collage Part 1: Fabric Collage By the Numbers #7, below, to understand how and why it’s not only logical but also optimal in how I work, using examples of both a butterfly wing and a sea turtle shell.

Tom and I are using part of our summertime to provide you with a sort of DIY Summer Collage Camp—or a Winter Collage Camp for those of you in the Southern Hemisphere. We’re calling it “Fabric Collage By the Numbers,” addressing all the steps of creating a fabric collage quilt. We hope you’ll participate from wherever you are in the world—no travel involved!

Pulling from six and a half years of fabric collage blog posts as reference material, we are delving into that content to give you a summertime lineup that you can follow along with. At the start of this series, there were eight weeks left of summer (not by the calendar but by the very subjective lens of the Maine climate!) so each week we’ll deliver two posts for a total of sixteen in the series—unless we re-discover more relevant posts along the way!

Posts from our Summer Special include; #1—choosing your photo (posted on July 7), #2—choosing a subject (posted on July 9), #3—making a pattern (posted on July 14), #4—how to choose fabric (posted July 16), #5—making a fabric palette (posted on July 21), #6—using glue as an adhesive (posted on July 23), to eventually hanging your fabric collage on the wall (planned delivery on August 27), we’ll cover each step with at least one previous post.

You may have read some of these posts before, so this will be a refresher for you. The information may also be reminiscent of information found in our online learning resource the Fabric Collage Master Class. If so, know that you’re not imagining things. Much of this information is gathered, reorganized and expanded upon in the Master Class. For more information about the Fabric Collage Master Class, click the button below.

Sequence in Fabric Collage Part 1

Something that isn’t obvious about fabric collage (as I teach it) is the importance of the sequence in which you approach the construction of your image. Where you start, and the order in which you proceed, can make a big difference in the ease of progress and outcome of your quilt.

Over the next few months I’ll be contributing to an ongoing series of blog posts that will discuss the best sequence to approach a fabric collage project using various quilt examples.

Recently I have been hard at work on my upcoming online eWorkshop, Susan Carlson Fabric Collage: Sea Turtle (above, in progress). The shell of a turtle presents thin lines in its design. It is similar in fact to another quilt I made, “Monarch Maia,” which features a portrait combined with the wings of a monarch butterfly.

The Monarch wings in that quilt were made in a very similar fashion to how I demonstrate making the shell on the sea turtle in the new eWorkshop.

In each case, panes or plates of color are surrounded by thin dark lines. Working the way I do, the full-size pattern based on your image is traced onto a plain foundation fabric. The temptation for many, when faced with such lines in their design, is to cut a dark fabric to cover the entire wing or shell first, then add the colored shapes on top.

The problem with this approach is that once you have placed the large dark color over the entire wing or shell, you’ve obscured the other shapes that you have drawn on your foundation fabric. How do you fill in those shapes if you’ve covered them up?

The answer would be a template approach—trace the shapes, number them, cut them out, pin them to your choice of fabrics, cut them out again, and figure out where to place them on that solid piece of fabric. Let me say right now that it’s not “wrong,” it’s just not how I approach fabric collage, and how I teach it.

I developed this form of fabric collage in my quest to make the process of creating an image in fabric more immediate, more painterly, less paint-by-numbers. I wanted to look at my subject and immediately respond by free-hand cutting and placing fabric directly onto a foundation fabric. Templates were, to me, a hindrance for how I wanted to work.

So how do I approach creating a butterfly wing or a sea turtle shell?

I start with the panes or plates first. Instead of creating these smaller shapes with one piece of fabric, I like to use several, depending on the size of the given area to fill. This to me gives the piece a richer more interesting look—like multiple dabs of paint—not at all the single color of a paint-by-number. As I glue the fabric pieces down I make sure that I leave their edges, especially those at the edge of the plate or pane, loose. Once the panes or plates are completed, I go back and slip strips of fabric between them and under the loose edges, again using not just one fabric for the contrasting lines, but as many as I like, depending on the look I’m trying to achieve.

In the photo below of the turtle shell from my eWorkshop, I’ve cut a sliver of brown and black fabric to slip into the gap between the plates. I have left the edges of the plates loose and cut the fabric sliver wider than the gap itself in order to ensure that the foundation fabric is covered and the gap is filled.

Here that sliver of fabric has been placed between the plates.

Note that I choose to vary the color and value of the fabric I use to fill the gaps. I do this to add interest, but more importantly to ensure that the plate and the gap fabrics have contrasting values. This is something that would be near impossible to preplan if you placed a large dark fabric down first then created the plates on top of it. And again, you’d need to resort to templates.

In the video excerpt below—a preview from the eWorkshop—I demonstrate how I choose, cut, place, and glue the strips of fabrics to fill the gaps between the plates on the turtle’s shell.

For another demonstration of this technique and other techniques for creating very fine lines, visit a previous blog post: “Get in Line: Skinny Lines in Fabric Collage.”

I like to work this way both because of the sense of (relative) immediacy it gives me and because of the customized results I get. Basically, ’cause I like the way it looks when I’m done.

Monarch Wing Example

In the following photos I show the sequence in which I approach the wings—specifically the lower part of the right wing—in this fanciful portrait of my niece, entitled “Monarch Maia.” I’ll be referring to the two parts of the right hand wing—please note that the lower part overlaps the upper part.

Below, the pattern I created has been traced onto a foundation fabric. My next step is to decide where to start. Where would you start?

Here’s the answer: you start with what is in front. I started with her face—specifically the nose, eyes, and mouth— because that is what is in front of the wings.

Now that the first draft of the face and then hair is done, I keep moving backwards on my subject to the wings, which are behind the hair. The lower right wing is in front of the rest of the wings, so I begin with that one. And on each part of the wings, I begin with the orange “panes.” Why? Because they are in front of the dark lines.

By choosing to work with the shapes that are in front of others first, I can see exactly where the orange shapes fit and what shape they should be. I retain the ability to work with my drawn lines and take full advantage of the work I put into the design.

I do use several pieces of fabric to fill each pane. The use of multiple fabrics allows me to blend easily from one value to the next—dark to light— and I feel the variety of prints gives a richness to the visual texture of the piece.

In the photo below I have completed a first draft of the orange panes on the lower right wing, but because of all the pins, I can tell they have yet to be glued in place.

I have also cut down groupings of “white” spots from another fabric, picked to represent the white spots of the Monarch wing edges—which are also in front of the black background of the wing. I leave a little of the black print surrounding the white spots, it saves me some work and will eventually blend with the rest of the black fabrics anyway.

All these fabrics shapes are still in front of the (eventual) black wing background. Here the first draft of the panes and white spots is complete. As I glue each piece of fabric onto the foundation, I tack only the centers with glue, leaving the edges loose, which will allow me to slip the dark fabrics behind either the orange or white shapes.

This way of construction makes sense to me and seems very logical—what’s in front overlaps what’s behind, right? Create the orange panes and white spots (what’s in front) first, then tuck the black behind.

Note in photo above the many different varieties and patterns of “black” I plan to use.

The first draft of the dark background is in progress above and below. It moves quickly since I’ve already done the work creating the orange and white shapes. The black bits of fabric just slip under those shapes and fill in the open spots on the foundation fabric.

Below, the first draft of lower wing is now complete. I make sure I’ve trimmed the black upper edge to my drawn line before I move on to the top wing section—the next area in my front to back sequence. Once that line is defined and the black fabrics secured with some glue (keeping edges loose), I can start tucking the orange fabrics of the upper part of the wing behind the lower part of the wing and repeat the process.

Below I’m making progress on the upper part of the front wing. The orange panes abutting that black edge tuck right underneath, the contrast creating a smooth, definitive division between the two parts of the wing. Check out more in-progress photos of “Monarch Maia” here.

Stay tuned for more examples of this—start with what’s in front—fabric collage construction sequence using other quilt subjects in following months.

Hi Susan. Your posts are so very helpful. Do you have any regarding faces?? How to choose the fabrics for a face? Where to start as far as choosing the colors?

Thank you so much for all the information you share. Sincerely,

Sandi Koterba

Hi Sandi! Stay tuned for tomorrow’s post, Saturday, July 30th—Sequence in Faces! Lots of info and links for more through my Thursday Night in my Studio videos. That should answer at least a few of your questions!

Thanks will check them out.