Winter rears its head and roars in a bit early. This week’s flight back home to Portland, ME from Madison, WI was delayed by a day because of winter storm Avery. (Glad they started using masculine names for storms. It seems only fair.)

Today’s post was supposed to be celebrating the three-year anniversary of my blog! But my travel adventures meant that Tom and I couldn’t collaborate as we would have liked, so we’ll postpone that idea until next week when, a look back at favorite blog posts of the year will make for a good Thanksgiving Weekend Special.

As proof that the snow has arrived, here’s a video Tom shot of our dog Kali, playing in the first snow of the season. She recognizes that snow means snowballs and she’ll quiver with excitement in anticipation. She loves snowballs. And then Tom added a couple pics of pups Kali and Felix, greeting me when I finally made it home yesterday afternoon.

In the meantime, I give you a repeat of one of my favorite posts of the past year. This blog post addresses big questions about art while providing concrete advice for helping you with your fabric collage quilt.

So enjoy this week’s selection and stay tuned for next week’s list of the top ten posts from our third year of blogging!

What Are Your Intentions? Fabric Collage with Intent

Fabric collage—indeed all art—is a reflection of the artist’s intent. Now, that might sound kinda fuzzy, kinda abstract and not very useful or practical. But let me expand on it a bit and see if I can change your mind.

Intent is so deeply buried in our appreciation of art that it’s almost invisible. Consider the cave paintings at Lascaux. Can you even begin to think about these 17,000-year old paintings of paleolithic animals and not wonder “Why?”

Another way to phrase the question is, “What was the artists’ intent?” They must have had a reason. Whether religious, ritualistic, or aesthetic, there was an intent driving the creation of these works. It seems foolish to claim that those long-ago artists had no motivation for descending into that cave with torches and pots of ground minerals to create these huge depictions.

Intent, I would say, is fundamental to art.

More importantly as an artist, defining or even simply being aware of one’s intent can be extremely helpful.

When a student in one of my fabric collage classes is struggling, the questions I find myself asking her often go into the story or intent. “What are you trying to say?” I ask. Or I tell her the story of what I see. “I really like this, it makes me think of this.” Or I might ask, “Did you want to do this? Because that’s what I’m seeing.” More often than not they say, “That’s exactly what I was hoping for!” So, I tell them to do more of that.

In essence I’m asking them to tell me the story of their quilt. My questions help them define or remind them of the narrative—the who, what, where and when—of the piece. (See “Telling the Story: Fabric Collage Backgrounds.”)

Without a clear intent, the work eventually bogs down. Why? Because of the infinite choices that face you when you don’t have a clear intent. The infinite is scary. It’s heavy. It’s impossible to carry around. The way to beat the infinite is with the specific.

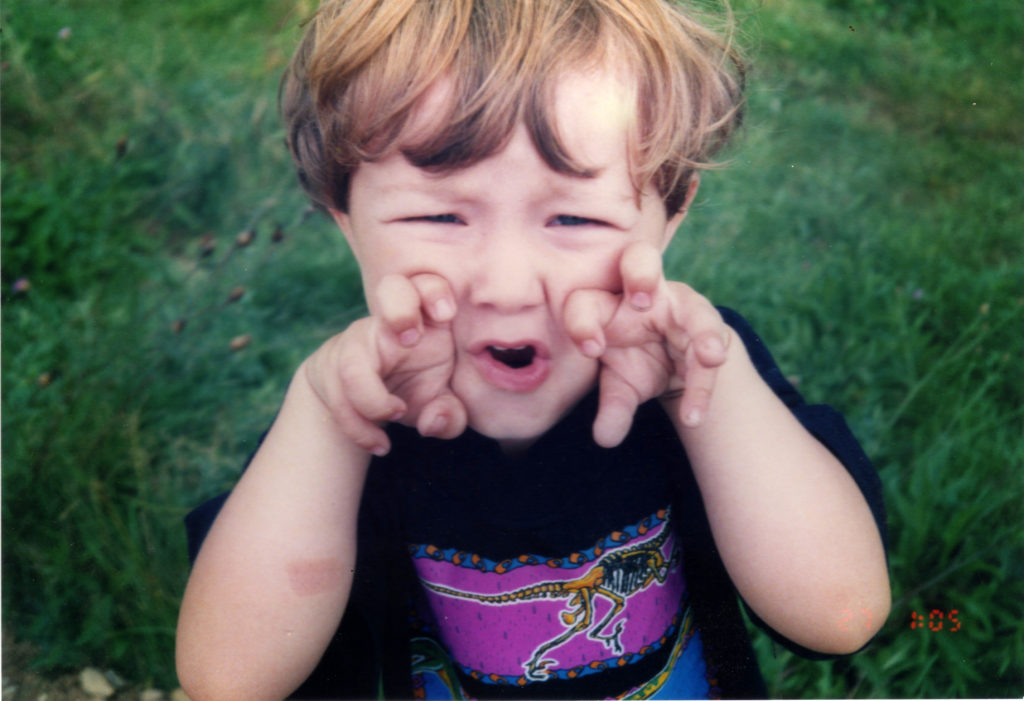

For example, when my son was three years old I took this picture of him and knew I had to make a portrait based on it.

So my intent at the most basic level was to create a portrait of my darling boy. But that wasn’t enough. There were infinite ways I could have proceeded. How would I choose? I had to further define my intent. Aside from creating a likeness of him as he pretended to be a dinosaur, I longed to capture the energy and enthusiasm, the spontaneity, of this moment. I also wanted to loosen up my style, which had grown kind of controlled and predictable. How could I do that?

I decided that my technique had to be as playful and energetic and spontaneous feeling as the image. So I chose an impressionistic style, and most importantly used scraps of collected fabric and laid them down with almost no cutting. “Samuelsaurus Rex” is the result.

My intention even extended to the binding, though it took my group of fabric artist friends to keep me on track. When I showed them the nearly-completed piece and told them I thought I would bind it with a red border, they all exclaimed that I couldn’t box in that energy. It needed to extend into and over the border. It shouldn’t be contained. So I used a wrapped and glued binding, bringing the image all the way to the edge and around to the back. No standard binding to enclose my little dino.

For my series of portraits “Farmer’s Market,” my source materials were a collection of photos I had taken over the course of almost two years. The Saturday market at a nearby parking lot was on my way to work. As the idea for the portraits grew in my head I began to take photos not just of the fruits and vegetables for sale but also of the people who grew and sold them. That was my first decision based on my intent.

Once I had the collection of photos and people, how would I choose which ones to portray?

I had to further define my intent. I wanted to represent the variety of produce sold, so I chose vegetables, eggs, flowers, and fruit. I decided that since it was a three-season market, I should try to capture the seasonal nature: there are spring, summer and fall veggies, flowers, and fruits.

Once my intent was clear, it narrowed down my choices, making the final selection manageable.

When I was a member of the Cocheco Quilt Guild in New Hampshire ages ago, one of the guild challenges was to represent the four elements—earth, air, fire, and water—in a quilt. The challenge was intentionally open to interpretation. To define my intent, I decided to personify the elements. If I were making the quilt nowadays, to find faces to use as models I might have been tempted to use a Google search, which would have made the selection process more difficult because of the almost infinite number of pictures to choose from. Luckily for me, this was in the pre-internet days, so I needed to use a source I had close to hand. Going through my own snapshots it became clear right away that most of my photos were of friends and family.

My task—or my intent—then was to choose a model for each element. In my own mind at least, I selected photos that displayed a trait I assigned to each element: the movement of the wind, the flourishing of the earth, the flow of water, the smoldering of fire.

My last choices were to decide on composition and color scheme. Since the four elements make up our planet, I decided they needed to encircle our big blue marble of a world in a full-spectrum range of colors. From there, it was simple to match each element with a primary or secondary color.

So let’s look at how my intent got more and more specific at each stage:

- Challenge from guild to represent the elements in a quilt.

- Decision to personify the elements in a quilt.

- Decision to use family and friends as models to personify the elements in a quilt.

- Decision to find a trait of each element in the photo of each model.

- Decision to encircle our planet with a color-wheel sort of effect—with a major color assigned to each element.

While still quite a challenge, the more specific my intent grew, the more manageable the task became.

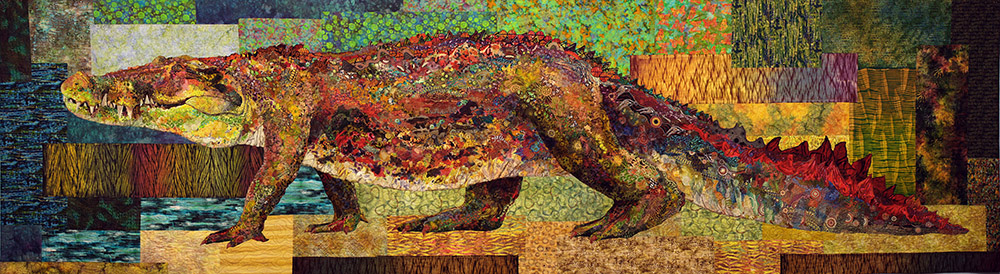

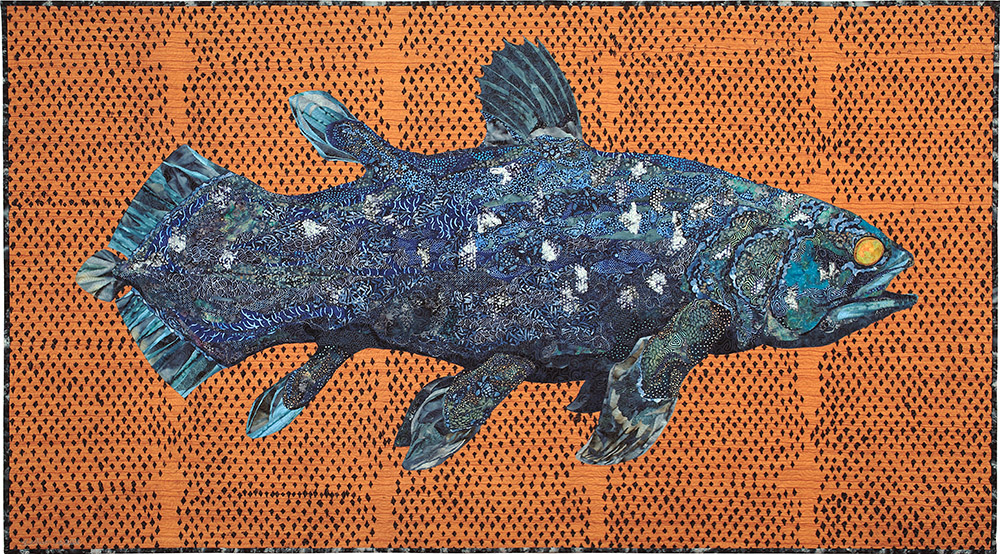

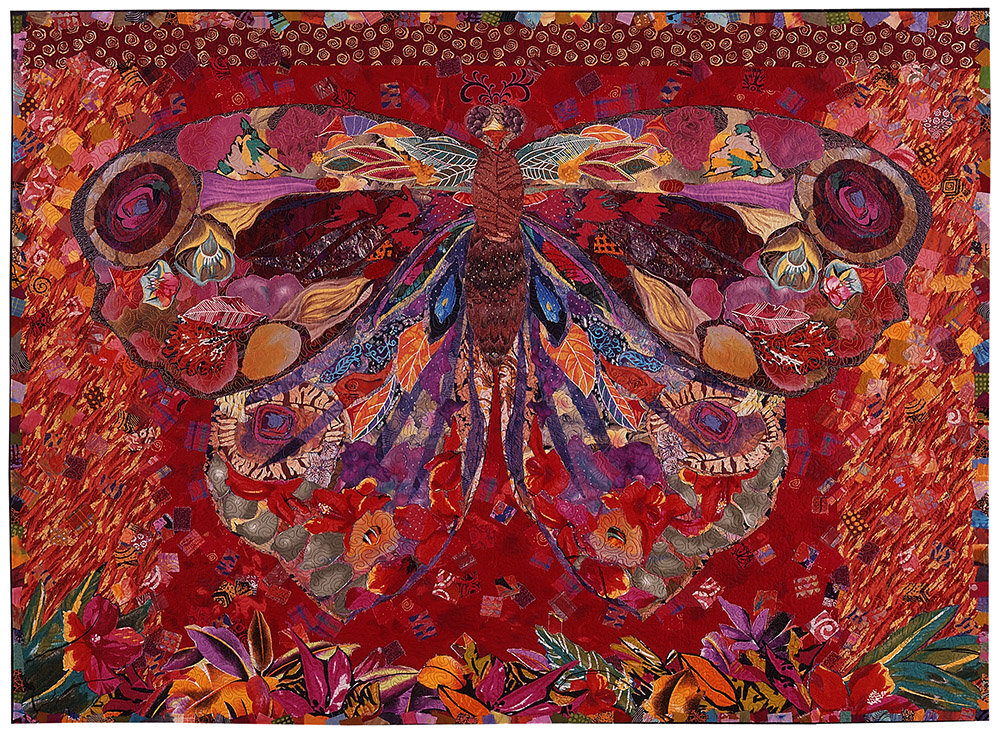

There is a range of intention as well. Intent can be broadly conceptual or simple and concrete. An example of a broad, overarching intent is my decision to create a group of quilts called “Specimens.” The organizing principle of this show is that each subject be “extinct, endangered, or otherwise unique—an animal with a story.” This intent helps me decide what quilt to make next. Of the whole world of possibilities for subjects, I know that I want to focus of these types of creatures.

“Specimens” Slideshow

On the other hand, intent can be very simple. Here are some examples from my Specimens quilts of simple decisions that made a huge impact on how I approached the construction of each:

- Choosing pink as the main color for the rhino in “Tickled Pink.”

- When I discovered that coelacanths were mottled blue and located in Indonesia, I decided to use Indonesian indigo batiks and only those batiks in the fish for “Gombessa.” Since they are also located off the coast of Africa, I used an African whole cloth print for the background.

- I used only novelty fruit printed fabric in my quilt of a fruit bat, “Fructos.”

- Learning that marabou storks feed mainly on carrion, I decided to create “Kaloli Moondance” entirely out of scrap fabrics.

- I was fascinated and awed by the average size of Australian saltwater crocs—twenty feet! I knew when I made my quilt “Crocodylus Smylus” it had to be twenty feet long.

- When doing a portrait of my dog Pippin, a “dixie dingo,” I chose to exclusively use Australian Aboriginal print fabrics.

Simple, sometimes arbitrary decisions—like making a rhino pink—define my intent, narrowing down the infinite to the specific. This is not to say that your intent has to be clear from the beginning, though it helps get the ball rolling. Thinking about your intent as you proceed, further defining it as you go, is also acceptable.

Sometimes, however, it’s not easy for me to determine intent. In part that’s why some projects have to gestate for so long. For example, it took years longer to start “Crocodylus Smylus” than it did to finish it once I had started. I need to find a way into the subject. Until I find that key—the right color or fabric or size or style—I can’t get going. I don’t consider this time wasted, however. Once I get an idea that I like, I believe my subconscious goes to work, slowly clarifying my vision—which is another word for intent.

Knowing our intent doesn’t do all the work for us, of course. We still have to do the labor of creating the quilt. But it can give us inspiration, direction, and focus.

Like that long ago paleolithic artist, it’s helpful to know our intent before crawling into the cave with our torch and pots of paint.

Fabric Collage Master Class

For instructions on the entire fabric collage process, you can purchase the Susan Carlson Fabric Collage Online Master Class Manual. Using video, photos, and text I take you from soup to nuts, beginning to end in creating your own fabric collage masterpiece.n

Your comments about intent are just what I needed to hear today to keep me from feeling useless during this percolating stage! And Kali is hilarious chasing snowballs! She looks puzzled that they disappear when she eats them. Such a precious girl.